Talkin’ Teleplasm: An Afternoon with the Mystical Medium (Scholar), Catherine van Reenen

Authored by Indiana M. A. Humniski

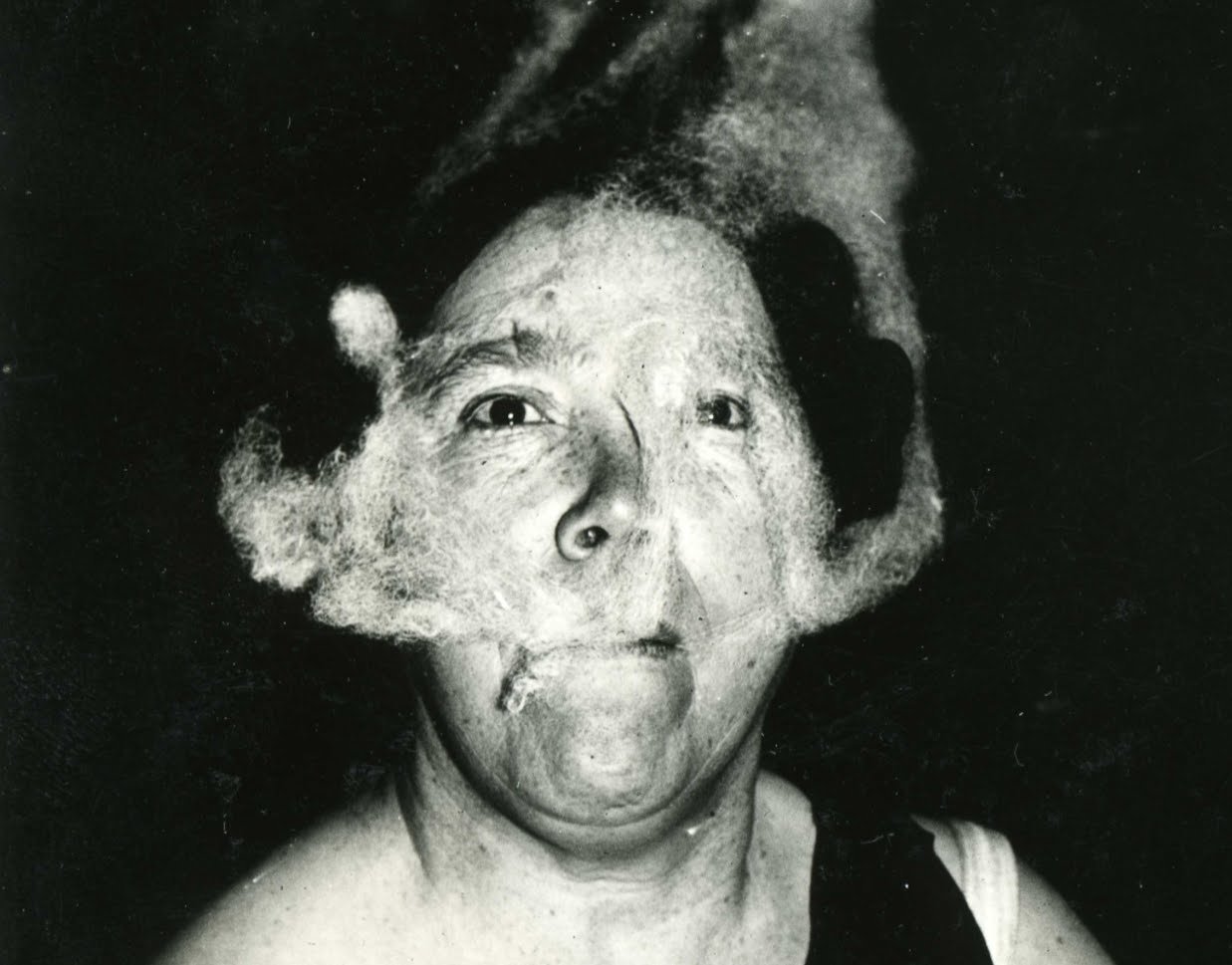

A photo of teleplasm or ectoplasm emanating from a medium, from the T.G. Hamilton collection in the U of M Libraries' Archives & Special Collections.

When Catherine van Reenen began her presentation by declaring, “Let’s get weird!,” I didn’t imagine that the session would end with her photographing me, in the dark, with kleenexes stuffed up my nose. I bet you’re wondering how I ended up in this situation; to get the answer, you’ll have to keep on reading or… wait for the spirits to send it to you!

In a flu-filled season where most people are worried about post-nasal drip, Catherine van Reenen is thinking about teleplasmic drip (which still, can ooze out from your nose). Rather than basing her presentation on the tempting yet troubling question of teleplasm's validity, van Reenen focuses on how its legacy spills across modern study. Teleplasm was a feature that arose out of spiritualism; spiritualism is a belief system that asserts deceased people are still able to communicate through the bodies of mediums. Catherine challenged her attendees to view spiritualism – like it was viewed by practitioners and believers in the nineteenth century – as a science. Van Reenen notes how all scientific concepts, one time or another, felt entirely unreal; from photography to x-rays, the Victorian period was filled with advancements that felt nearly magical in their extreme distance from what society had experienced before.

Illustrated interior of the Crystal Palace during the Great Exhibition of 1851. This exhibition featured numerous global advancements in technology, material culture, and featured the treasures and triumphs — often, troublingly gathered — within the British imperial empire. To hear more about this era, this exhibition (and the thrilling story of a colonially-stolen diamond), listen to S3 : E5 of the Victorian Samplings podcast wherever you stream podcasts. Image sourced from the London Museum.

Thus, spiritualism mimicked the unbelievability of other innovations at the time. Both spiritists and psychical researchers alike believed that – when they were trying to communicate with the other side – they were interacting with science. Although this field has been plagued with disbelievers since its very dawn, University of Manitoba’s own Marshall McLuhan included, van Reenen proposes that the argument of spiritualism as a pseudo-science falls upon its proverbial (perhaps, oozing) face.

We can imagine spiritualism hanging over Victorian society as thickly as London’s city smog; it was a phenomenon that one could not ignore. It had a simultaneous allure and, perhaps, a fear-filled aura of unnaturalness. One thing that is decidedly not unnatural though is the desire to communicate with one’s loved ones, even from beyond the grave. This is the sympathetic note that spiritualism hits most poignantly. Mediums provided not only a sense of scientific gravitas but, importantly, a sense of comfort to the grieving. There is clearly a strong thread of emotion stitched into the existence of mediums across the centuries; this thread is tugged upon, rather harshly, by some of the field’s critics.

The title of medium entails someone, typically a woman, who could communicate with the spiritual realm. It is the particular method of communication that deeply intrigues van Reenen. In Catherine and I’s favourite era – the Victorian period – mediums expressed messages from spirits in various ways. She explained how there were professionals who specialized in speaking, writing, clairvoyance, clairaudience, drawing, interacting with lights, rapping noises (like a telegraph, unfortunately not in the Kendrick Lamar fashion), impersonating, and even – to the delight of a fellow Victorianist in attendance, Dr. Vanessa Warne – typewriting!

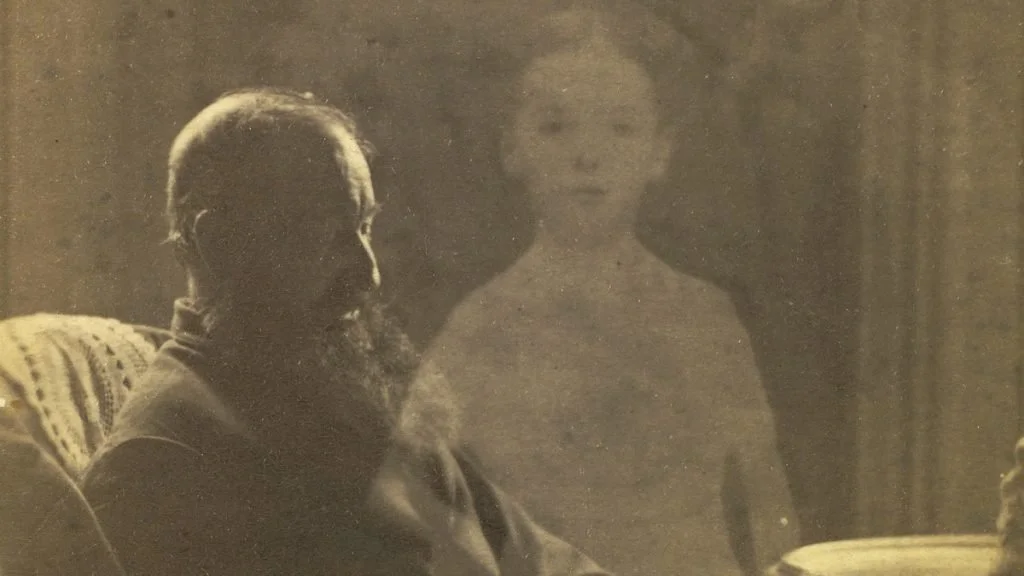

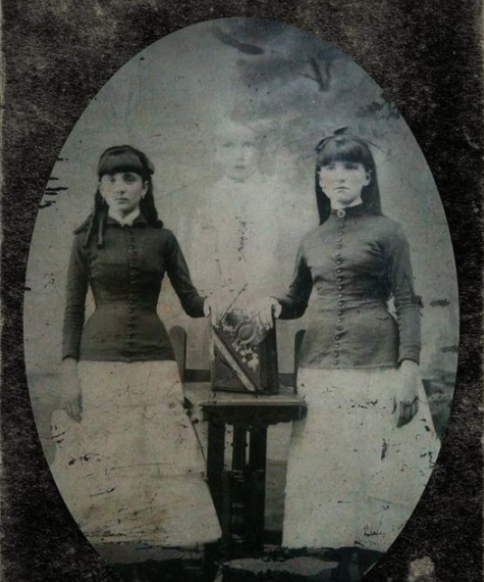

Unidentified Man Seated with a “Spirit”, sourced from the J. Paul Getty Museum.

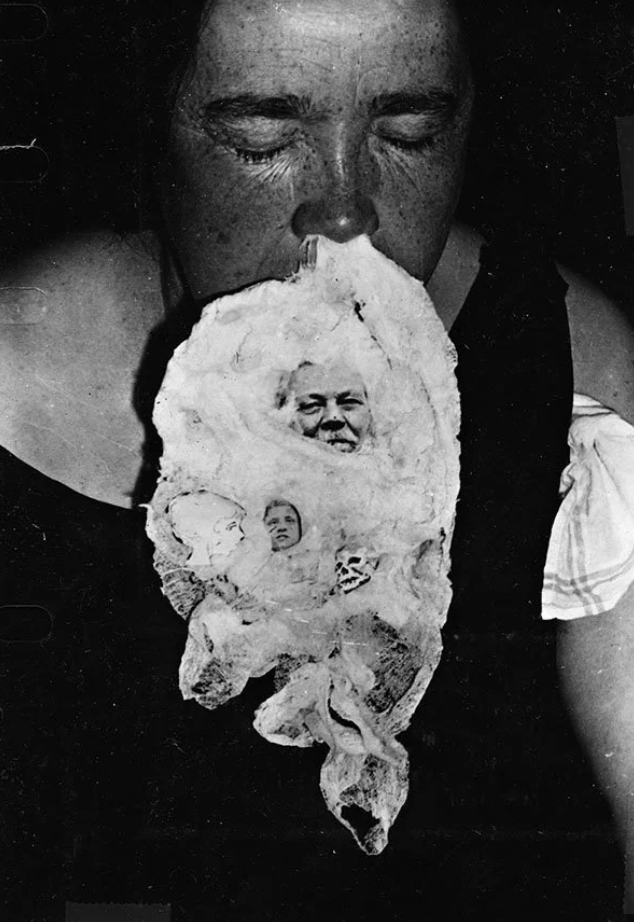

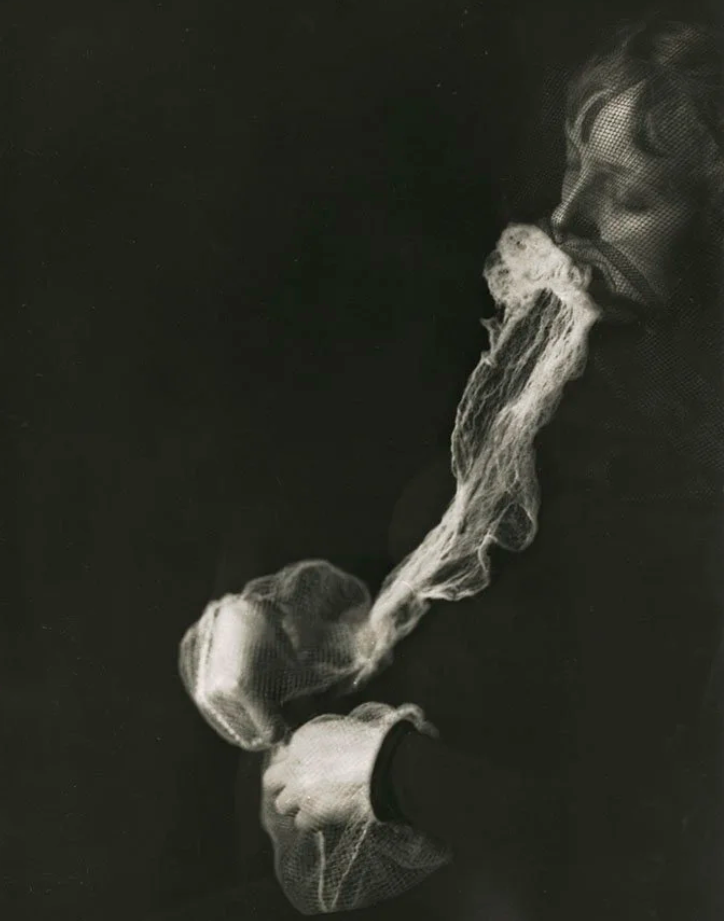

Catherine quickly honed in on the primary form of mediumship we would be focusing on today: materialization mediums. In this vein of medium-ship, it is now time to talk teleplasm. Teleplasm is a substance that is, essentially, spiritual communication manifested into a material form. This cloudlike cascade emerges from various orifices including but not limited to the medium’s mouth, nose, or – perhaps, most eerily – their eyes. When photographed, it may contain photographic representations of human beings. A better-known image showcasing this feature includes Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the infamous creator of Sherlock Holmes and dedicated spiritist who actually attended seances in Winnipeg! With the uncontrollable nature of teleplasm, it seems to present itself almost like a child. It is chaotic, tumbling, and contains traces of humanity – beyond its own age. Like the troublesome twos of a toddler, teleplasm also seems like an unruly force to be reckoned with.

Medium Mary Marshall, with teleplasmic mass featuring the faces of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Photographed by Dr. Thomas Glendenning Hamilton, 1932.

Medium Stanisława P. projecting an ectoplasmic substance through her mouth (under netting). Photographed by Albert von Schrenck-Notzing, 1913.

This spooky substance is defined within two contrasting schools of thought. Animists argue that it stems from a “previously-unknown psychic force within the medium” and the medium's own subconscious. Alternatively, spiritists think the material to be “the result of disembodied intelligences using materials drawn from the medium’s body” that actually does represent communications from an “immaterial plane of existence” or, put more simply, from spirits themselves. I would argue that the argument of the spiritists is, indeed, more enticing in the Halloween season that van Reenen presented within; it is comparable to possession, an invasion of the body – however willingly yielded by the medium themselves.

Teleplasm can also be referred to (and admonished) as another name: ectoplasm. To my father’s chagrin, the presentation turned away from Ghostbusters and, instead, towards the similarly-renowned figure of Marshall McLuhan. Raised right here in Winnipeg, McLuhan was a Canadian philosopher who provided cornerstone texts that shaped the field of media theory. McLuhan died on December 31st, 1980; however, I would venture to guess that he, although being a prolific thought-sharer while alive, would be against us summoning a medium to ask him his thoughts from beyond the grave.

A slide from van Reenen’s presentation, featuring the original Manitoban clipping.

Van Reenen showed her attendees an article penned by McLuhan himself for our own school paper, The Manitoban. The general theme of this article is McLuhan’s argument that that Spiritualists engage with the spirit world superficially, without “desire to reform the lives or ways of men.” He further characterizes mediums themselves as "primitive types” in an problematic way. He refers to these mediums as possessors of a “vestigial sixth sense” – describing an ability that is not essential to life, something that has evolved to being “functionally useless” over time. He doubles down on this dictionary-based definition of a vestigial organ by summatively declaring how spiritualism is “an excellent subject for research, but it is nothing more.” This analysis reads as definitively “icky” – in media studies, what is “icky” is denigrated as low-brow. Van Reenen’s use of the word “icky” may remind us of teleplasm itself – something that she describes as concurrently “strange, abject, [and] spectacular.” Van Reenen further argues that the “extension of the self” that McLuhan mentions in regard to media studies can be easily linked back to teleplasm. Indeed, the substance is a literal extension from within the body – whether from the medium’s unconscious or spiritual influences – that emerges into the outside world. Thus, while one of McLuhan’s iconic statements was “the medium is the message,” I am certain that he didn’t mean medium in the spiritual sense.

McLuhan is far from being the sole critic when it comes to the concept of spiritualism; however, van Reenen focused upon him due to her status as an academic in Media Studies. While many folks like McLuhan may easefully criticize the concept of mediums as a whole, van Reenen wants us to focus on another less-easeful factor: the grotesque. She pondered how “a talking ghost is plausible, a writing ghost – okay sure, but a materializing ghost is where a lot of people, including a lot of spiritualists and psychical researchers, draw the line. It is literally too gross, too material.” The concept of a ghostly presence being “material” is where the freaky factor is found.

A smattering of spirit photographs, three selected out of thousands of examples.

Imagine this for a moment. I’d ask you to close your eyes but, of course, then you wouldn’t be able to read my next instructions. Imagine a dark room, heady with the perfume of someone unseen. It is an old-fashioned scent, lemon verbena, a smell more suited to a time now past rather than the audiences of today’s world. It smells like springtime, not like the winters of Winnipeg. Perhaps, you are smelling a spirit, somewhere in the room. Are you frightened? Perhaps, not as much as you could be.

Now, imagine you’re in an Open House; the realtor is pressing pamphlets into your hand and declaring that, buying or selling, they’ll get you moving just fine. Suddenly, walking up the stairwell to the attic, you pass by a bay window with a half-drawn curtain. In your haste, you can almost swear that you saw a shadow sitting there, perched down as if paused mid-chapter. It is an easeful pose. As soon as you convince yourself to look back, the shadow – or, whatever it was – is gone. Are you frightened now?

Alright, final scenario: you are suddenly in the nineteenth century, air thick with the smell of roasted ham, city smog, and… perhaps… lemon verbena? You are sitting down at a table, covered with a cloth, with a medium seated at the head. She inhales gently, her breath becoming the sole sound in the dark. Your neighbors hold their own as you await the dreadful sight that you had been promised. She whispers in a low murmur, unintelligible to your ears. Suddenly, with a flashing light of a camera’s bulb, your hand involuntarily comes up to shield your eyes. Thus, you won’t see what the flash has captured until the photograph is developed, perhaps weeks later. Then, you’ll see it. A white material that is dripping, dropping out of the woman’s body as if her own intestines had suddenly been pushed from between her lips. The papers have been calling it teleplasm; you hadn’t believed in it until this moment. As you look closer, fighting disgust and rising nausea, you see something that you recognize. The face of your recently-deceased loved one is present in the image, suspended in the metamorphic goo that hangs around the medium’s neck like a cameo necklace. They look just like they did the last time you saw them alive, just like the photograph that you handed over to the medium before the seance. Your loved one will now sit there, stuck forever, in a liminal space between material states of being.

It is too, too grotesque.

It is too, too horrible.

And yet, it is too, too impossible to look away.

Now, I’ll ask once more… Are you frightened?

Perhaps, I can quell this fear by, finally, telling you about my own teleplasmic portrait. Teleplasm is a “wild, uncontrollable force” according to van Reenen but, with her simple steps, it becomes something that one can capture with their own phone.

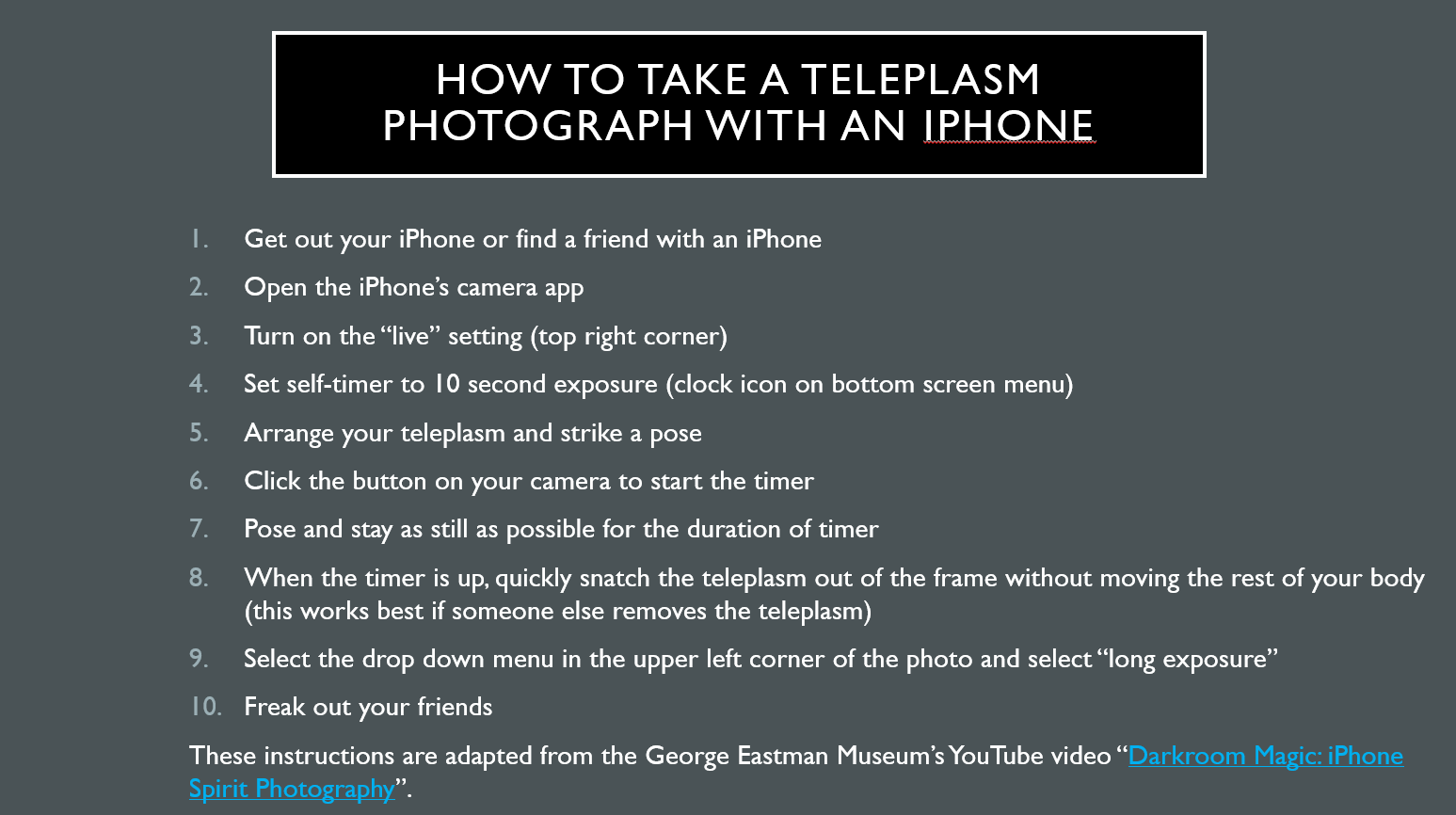

Van Reenen’s easy steps to snag your own spirit photograph! To access the YouTube video that van Reenen mentions, simply click here.

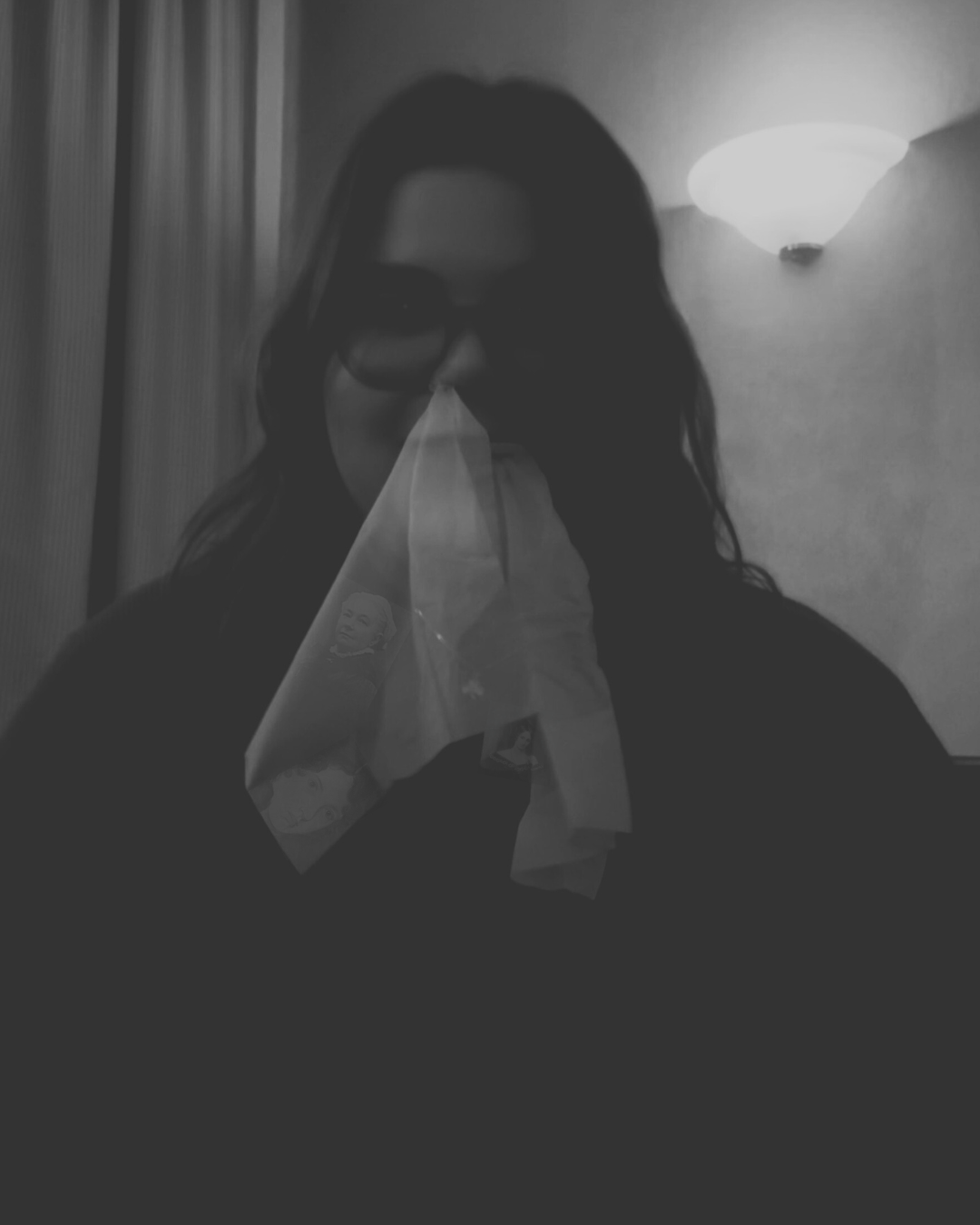

Firstly, Catherine asked for volunteer mediums; of course, I jumped at the opportunity. While this wasn’t the Theresa-Caputo-style vibes that I was used to, I was excited to step into the realm of the Victorian period. I sat down in the plush chair of 409 Tier, right next to the projector. It felt somewhat silly to be next to such a modern invention while engaging hands-on with the past. I battled the kleenex dust and placed the tissues in both my nostril and my mouth. Whilst sitting there for ten seconds of photographic exposure, I felt a fleeting kinship with the famously unsmiling faces of the Victorian period. Still, with two kleenexes placed in my nose and lips respectively, it felt difficult to suppress a smile. When van Reenen swapped the effect to “long exposure,” the instinct took over; the photograph was eerie, gothic, and enticingly ethereal. I had taken one small step away from 409 Tier and one giant leap towards the shadowy spectacles of the Victorian period. While I cannot accurately say that the likenesses of Charlotte Bronte, Mary Shelley, and Margaret Oliphant appeared by any ghostly interference, I certainly felt a little chill of excitement and confusion staring at the final outcome.

The result of my DIY teleplasmic portrait. Thank you, Catherine, for showing us this creative process and — of course — for being there to catch my kleenexes.

As the ghosts of autumnal breezes give way to nose-numbing cold, perhaps it is now time to embrace the unembraceable. Perhaps, it is time to get a little ghostly in the comfort of your own home or, rather, in the dark, dark boardroom of the Tier building with a colleague ready to pull kleenexes out of your face.

(Article written in late October, 2025)